[Part 1] Six modern software architecture styles: Monolithic

Leveraging tried-and-tested solutions saves time, ensures reliability, and helps avoid common pitfalls. We look at six common architectural styles used in distributed systems and talk about how to choose the best one for your use case.

![[Part 1] Six modern software architecture styles: Monolithic](https://www.multiplayer.app/blog/content/images/size/w1200/2025/11/monolithic.png)

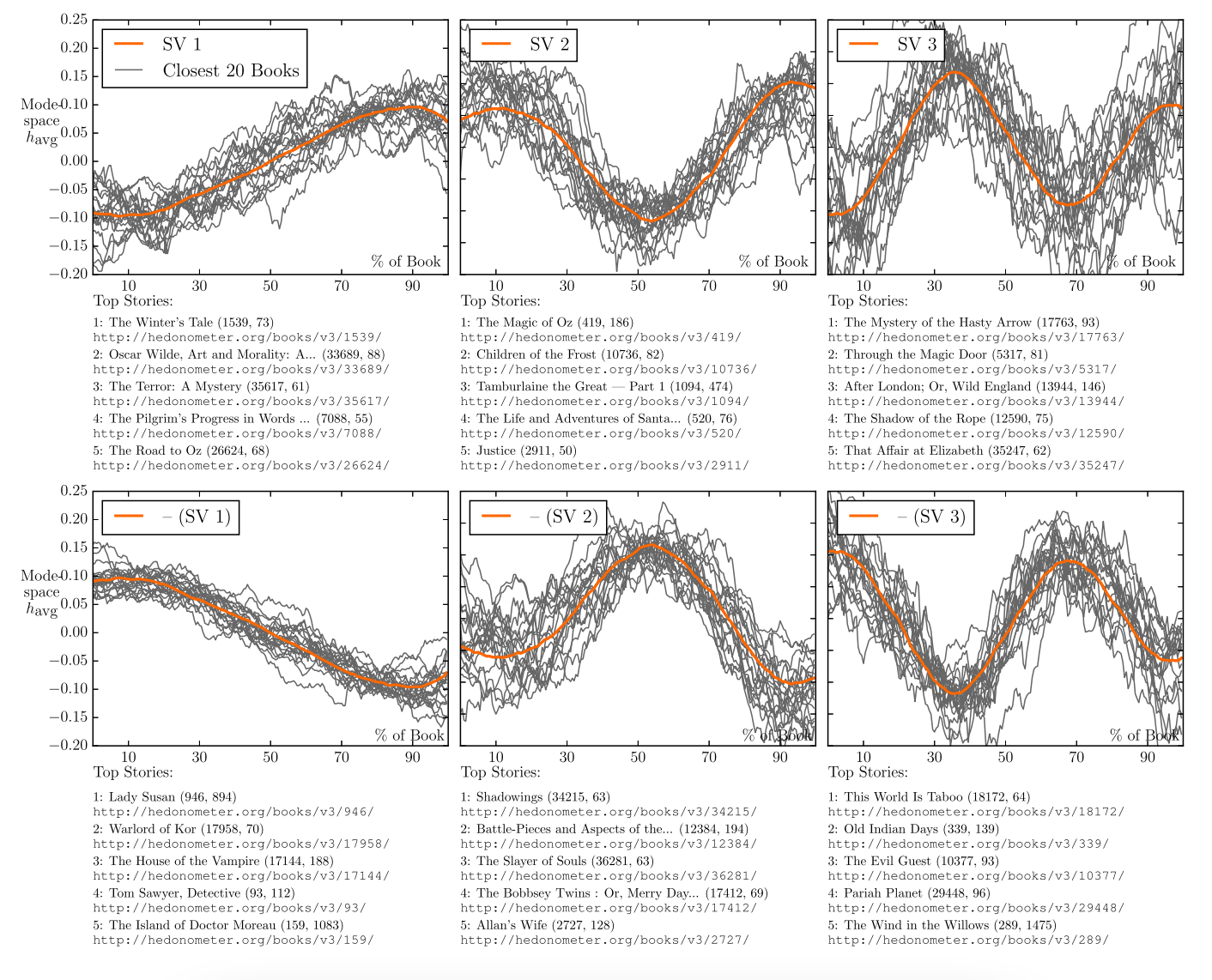

In 2016 researchers at the University of Vermont applied matrix decomposition, supervised learning, and unsupervised learning to a data set of 13,000 popular stories. They discovered that each story followed the pattern of one of six basic plots.

If we were to analyze the most common software architecture designs used in modern applications, what patterns would emerge?

Just as popular stories tend to have common narrative structures, distributed software systems often exhibit recurring architectural patterns. These patterns emerge because they provide effective solutions to common design and implementation challenges.

However, just as storytellers balance the use of conventional story structures with innovative elements to create unique narratives, engineers balance the use of well-established architectural patterns with innovative solutions to craft use case-specific software systems.

In this blog post series we’ll look at six common architectural styles used in distributed systems and talk about how to choose the best one for your use case.

Modern Architectural Styles for Distributed Systems

Architectural styles are often characterized in opposition with each other. The monolith vs microservices dichotomy is well-known. But the truth is that each has a specific use case and most often they coexist together in a company’s portfolio of applications.

“I kind of feel like microservice-vs-monolith isn’t a great argument. It’s like arguing about vectors vs. linked lists or garbage collection vs. memory management. These designs are all tools — what’s important is to understand the value that you get from each, and when you can take advantage of that value. If you insist on microservicing everything, you’re definitely going to microservice some monoliths that you probably should have just left alone. But if you say, ‘We don’t do microservices,’ you’re probably leaving some agility, reliability and efficiency on the table.”

- Brendan Burns, co-creator of Kubernetes, now corporate vice president at Microsoft.

Leveraging tried-and-tested solutions saves time, ensures reliability, and helps avoid common pitfalls. There is no doubt that businesses can reap these benefits from a well-designed software architecture, along with others, which include:

- Rapid development → Developers can focus on implementing application-specific features rather than struggling with fundamental design decisions.

- Consistency and standardization → Multiple team members can easily maintain a shared understanding of the system's structure and collaborate on it.

- Improved maintainability → Architectural styles promote clean, modular, and organized software, making it easier to maintain and update over time.

Building an evolvable architectural software system is a strategy. It requires experience, intuition, flexibility and foresight to select the right patterns - or the right “story plots” - that will serve your audience best.

In this post series we review these six popular architectural styles:

(1) Monolithic

(2) Microservices

(3) Event-Driven

(4) Serverless

(5) Edge Computing

(6) Peer-to-Peer

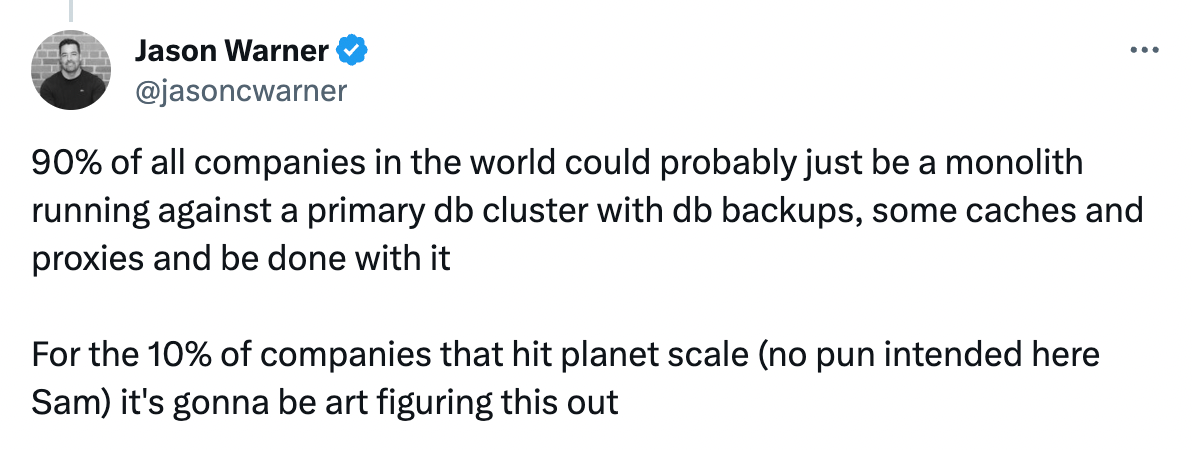

Choosing the Best Architectural Style for You

"… the startups we audited that are now doing the best usually had an almost brazenly ‘Keep It Simple’ approach to engineering. Cleverness for cleverness sake was abhorred.”

- Ken Kantzer, Co-founder and CTO of Truss, former VP of Engineering at FiscalNote

Building distributed systems is not easy: everything - from development, debugging, deployment, testing - is more challenging and time-consuming. When given a choice, the best approach is to keep it simple - boring even!

Even when leveraging tried and tested architectural styles, there is no default approach to building a distributed system: it will always depend on your application. You will have to clarify the business outcomes you’re looking to achieve, considering the various tradeoffs of one decision over another, and calculating the design benefits.

Ultimately, you’ll likely end up using a hybrid architecture, combining elements of multiple architectural styles as they make most sense for specific parts / features of the application. For example, you may start with a well-modularized monolith, add a few microservices for new features or design them as serverless due to their spiky workloads.

One immutable truth of system design is that systems are mutable and ever evolving. You should always seek to refine, simplify, and improve the architecture of the system, as the needs of your organization change, the IT landscape evolves, and the capabilities of selected providers expand.

Regardless of the software architecture style you choose, remember that software systems live and breathe and change. A dead, ossifying software system will rapidly bring an organization to a standstill, preventing it from respond to new threats and opportunities.

(1) Monolithic Architectural Style

One-liner Recap:

Everything is in one, easy box.

Background:

In the early days of software development, monoliths were the norm - all components were tightly integrated within a single codebase and runtime environment.

However, in the 2000s the concept of Service-Oriented Architecture (SOA) started to gain traction, because of some of the more painful aspects of monolithic deployments exemplified with the 1999’s Big Ball of Mud description put forth by Professors Brian Foote and Joseph Yoder.

To be clear, the initial idea of the Big Ball of Mud doesn’t match the current image of monoliths: a tower of rigid, inflexible, tightly-coupled processes, where deploying a simple change to one part of the app may inadvertently affect a totally different one. It was actually aiming to describe a chaotic architecture made up of programs haphazardly heaped onto other programs, with data exchanged between them by means of file dumps onto floppy disks.

Nonetheless the assertion that “monolith” unequivocally means “big ball of mud” led to the resurgence in other systems architecture styles. However, the Monolithic Architecture can (and, in some cases, should) still be used in modern distributed systems.

Weaknesses:

In recent years, there has been a stigma associated with starting your project with a straight-forward, simple, performant monolith.

This stems, in part, from traumatizing experiences of trying to work with legacy big-ball-of-mud monoliths, where every test is tedious, understanding the code is hard, and deployments are unreliable. And also, in part, from the need to try the latest technologies and match the industry’s expectations for “modern” approaches.

While it’s absolutely true that some monolith deployments become unwieldy when working with complex applications, the solution is fairly simple and well known (and, arguably, easier to implement than microservices): breaking monoliths down into modules - semi-independent components. A core concept that has been at the heart of most programming languages since the 1970s.

Modern tooling has also evolved to address monolith maintenance challenges. Full stack session recordings transform debugging workflows by capturing the complete user journey (from frontend interactions through backend traces, logs, request/response content and headers), eliminating the guesswork that often makes legacy monolith debugging so painful. This visibility into the entire request lifecycle helps teams avoid the 'tedious test, hard-to-understand code' trap that gives monoliths their bad reputation.

Strengths:

“For 95% of the software we build, a simple monolith with easy-to-understand code is the right choice. Could we be more fancy? Sure, but to what end? We have a responsibility to the people that come after us and maintain things. I tell our team all the time that they will never impress me with clever code or architecture. A simple to read and understand chunk of code that solves a problem clearly and effectively; now that is the manifestation of mastery!”

- Keith Warren, CEO of Fern Creek Software

If you’re a single small-to-medium team, with a monolithic architecture you can effectively develop, test, deploy, and maintain your app, even if it’s a large code base. By leveraging properly deployed modules, you can keep coupling to a minimum. Since everything is in one place, it’s easier to track down issues and fix them. You can also drastically reduce redundant boilerplate and write DRY (Don’t Repeat Yourself) code. That's not insignificant when it's one of the hardest best practices to apply in a microservices architecture.

If / when you have a multimillion line codebase that starts requiring a few sacrifices to the gods and several days for a deploy, at that point you can break it into services or start considering a microservices architecture. In 2015, in Martin Fowler’s “MonolithFirst” essay, he writes that a reasonable method for arriving at a microservices system is to begin with a monolith and peel away microservices individually and carefully.

Lastly, remember that before we had “microservices” we used to rely on “trunk based development” where the main monolith (trunk) was helped by “branch” services. Or as David Heinemeier Hansson, CTO and co-founder of Basecamp, called it “the pattern of The Citadel: A single Majestic Monolith captures the majority mass of the app, with a few auxiliary outpost apps for highly specialized and divergent needs.”

Real-world use cases:

Dropbox, X (Twitter), Netflix, Facebook, GitHub, Instagram, WhatsApp. All these companies and many others started out as monolithic code bases. Many large enterprises still rely on them to this day. For example: Istio, Segment, StackOverflow, and Shopify.

👀 If this is the first time you’ve heard about Multiplayer, you may want to see full stack session recordings in action. You can do that in our free sandbox: sandbox.multiplayer.app

If you’re ready to trial Multiplayer you can start a free plan at any time 👇