Six best practices for backend design in distributed system

Most modern software systems are distributed systems, but designing a distributed system isn’t easy. Here are six best practices to get you started.

Most modern software systems are distributed systems. Designing and maintaining a distributed system, however, isn't easy. There are so many areas to master: communication, security, reliability, concurrency, and, crucially, observability and debugging.

When things go wrong (and they will as we've seen recently and repeatedly), you need to understand what happened across your entire stack.

Here are six best practices to get you started:

(1) Design for failure (and debuggability)

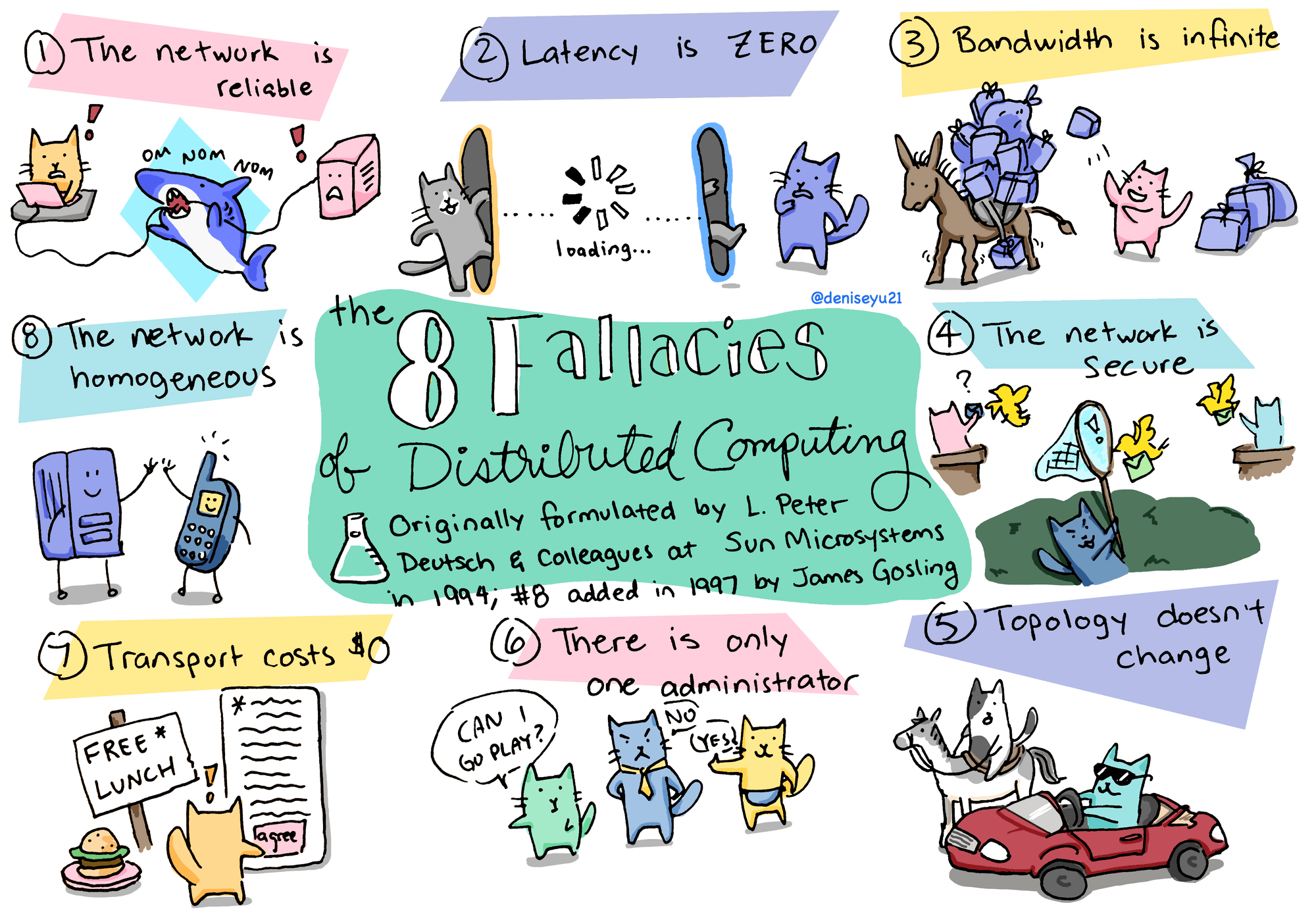

Failure is inevitable in distributed systems. Most of us are familiar with the 8 fallacies of distributed computing, those optimistic assumptions that don't hold in the real world. Switches go down. Garbage collection pauses make leaders "disappear." Socket writes appear to succeed but have actually failed on some machines. A slow disk drive on one machine causes a communication protocol in the whole cluster to crawl.

Back in 2009, Google fellow Jeff Dean cataloged the "Joys of Real Hardware," noting that in a typical year, a cluster will experience around 20 rack failures, 8 network maintenances, and at least one PDU failure.

Fast forward to 2025, and outages remain a fact of life:

- November 18, 2025 - A bug in Cloudflare's Bot Management system caused widespread disruption across many web services

- October 20, 2025 - An AWS disruption in the US-East-1 region affected thousands of applications

- April 28, 2025 - A power-grid collapse in Spain and Portugal disrupted electric, telecommunication, and transport services across the Iberian Peninsula

The lesson? Design your system assuming it will fail, not hoping it won't. Build in graceful degradation, redundancy, and fault tolerance from the start.

But resilience isn't enough. You also need debuggability. When (not if) failures occur, your team needs answers fast:

- What triggered the failure? The user action, the API call, the specific request that started the cascade

- How did it propagate? Which services were involved, what data was passed between them, where did things go wrong

- Why did it happen? The root cause. Whether in your backend logic, database queries, or infrastructure layer

This requires capturing complete technical context, not just high-level signals. Aggregate metrics and sampled traces tell you something is wrong. Full context tells you exactly what went wrong and why.

Traditional monitoring gives you: "The system is slow."

What you actually need: "This specific user's checkout failed because the payment service timed out waiting for the inventory service, which was blocked on a slow database query."

The difference between these two statements is the difference between hours of investigation and minutes to resolution.

(2) Choose your consistency and availability models

Generally, in a distributed system, locks are impractical to implement and difficult to scale. As a result, you'll need to make trade-offs between the consistency and availability of data. In many cases, availability can be prioritized and consistency guarantees weakened to eventual consistency, with data structures such as CRDTs (Conflict-free Replicated Data Types).

It's also important to note that most modern systems use different models for different data. User profile updates might be eventually consistent, while financial transactions require strong consistency. Design your system with these nuances in mind rather than applying one model everywhere.

A few more considerations:

Pay attention to data consistency: When researching which consistency model is appropriate for your system (and how to design it to handle conflicts and inconsistencies), review foundational resources like The Byzantine Generals Problem and the Raft Consensus Algorithm. Understanding these concepts helps you reason about what guarantees your system can actually provide and what it can't.

Strive for at least partial availability: You want the ability to return some results even when parts of your system are failing. The CAP theorem (Consistency, Availability, and Partition Tolerance) is well-suited for critiquing a distributed system design and understanding what trade-offs need to be made. Remember: out of C, A, and P, you can't choose CA. Network partitions will happen, so you're really choosing between consistency and availability when partitions occur.

(3) Build on a solid foundation from the start

Whether you're a pre-seed startup working on your first product, or an enterprise company releasing a new feature, you want to assume success for your project.

This means choosing the technologies, architecture, and protocols that will best serve your final product and set you up for scale. A little work upfront in these areas will lead to more speed down the line:

Security: A zero-trust architecture is the standard: assume breaches will happen and design accordingly to minimize your blast radius.

Containers: Some may still consider containers an advanced technique, but modern container runtimes have matured significantly, making containerization a default choice

Orchestration: Reduce the operational overhead and automate many of the tasks involved in managing containerized applications. Kubernetes has become the de facto standard, but for smaller teams, managed container services (AWS ECS/Fargate, Google Cloud Run, Azure Container Apps) offer simpler alternatives without sacrificing scalability.

Infrastructure as code: Define infrastructure resources in a consistent and repeatable way, reducing the risk of configuration errors and ensuring that infrastructure is always in a known state. Tools like Terraform, Pulumi, and AWS CDK make infrastructure changes reviewable, testable, and version-controlled.

Standard communication protocols: REST, gRPC, GraphQL, and other well-established protocols simplify communication between different components and improve compatibility and interoperability. Choose protocols that match your use case: REST for simplicity, gRPC for performance, GraphQL for flexible client needs.

Observability from day one: Don't treat logging, metrics, and tracing as something you add later. Build observability into your system from the start, including structured logging, distributed tracing, and comprehensive session recording. When issues arise (and they will), having this context already in place is the difference between quick resolution and prolonged outages.

(4) Minimize dependencies

If the goal is to have a system that is resilient, scalable, and fault-tolerant, then you need to consider reducing dependencies with a combination of architectural, infrastructure, and communication patterns.

Service Decomposition: Each service should be responsible for a specific business capability, and they should communicate with each other using well-defined APIs. Start with a well-modularized monolith and extract services only when you have clear reasons (team autonomy, different scaling needs, technology requirements).

Organization of code: Choosing between a monorepo or polyrepo depends on your project requirements. Monorepos excel at atomic changes across services and shared tooling, while polyrepos provide stronger boundaries and independent versioning. Modern monorepo tools (Nx, Turborepo, Bazel) have made the monorepo approach increasingly viable even at large scale.

Service Mesh: A dedicated infrastructure layer for managing service-to-service communication provides a uniform way of handling traffic between services, including routing, load balancing, service discovery, and fault tolerance. Service meshes like Istio, Linkerd, and Consul add complexity (so evaluate carefully whether you actually need one!) but solve real problems at scale.

Asynchronous Communication: By using patterns like message queues and event streams, you can decouple services from one another. This reduces cascading failures: if one service is down, messages queue up rather than causing immediate failures. Tools like Kafka, RabbitMQ, and cloud-native options (AWS SQS, Google Pub/Sub) enable this decoupling.

Circuit breakers and timeouts: Implement patterns that prevent cascading failures. When a downstream service is struggling, circuit breakers stop sending it traffic, giving it time to recover. Proper timeouts prevent one slow service from tying up resources across your entire system.

(5) Monitor and measure system performance

In a distributed system, it can be difficult to identify the root cause of performance issues, especially when there are multiple systems involved.

Any developer can attest that "it's slow" is and will be one of the hardest problems you'll ever debug!

In recent years we've seen a shift from traditional Application Performance Monitoring (APM) to modern observability practices, as the need to identify and understand "unknown unknowns" becomes more critical.

Traditional APM tools excel at answering questions you already know to ask: "Is the database slow?", "What's the error rate?", etc. But struggle with the unexpected, hard-to-reproduce and understand issues that plague distributed systems. That's why modern observability focuses on capturing complete context about system behavior.

Rather than just collecting aggregate metrics and sampled traces, comprehensive observability tools capture:

- Complete request traces across your entire distributed system, not just statistical samples

- Full session context showing what users actually did, not just backend telemetry

- Detailed interaction data including request/response payloads, database queries, and service call chains

- Correlated frontend and backend behavior so you can see how user actions translate to system load

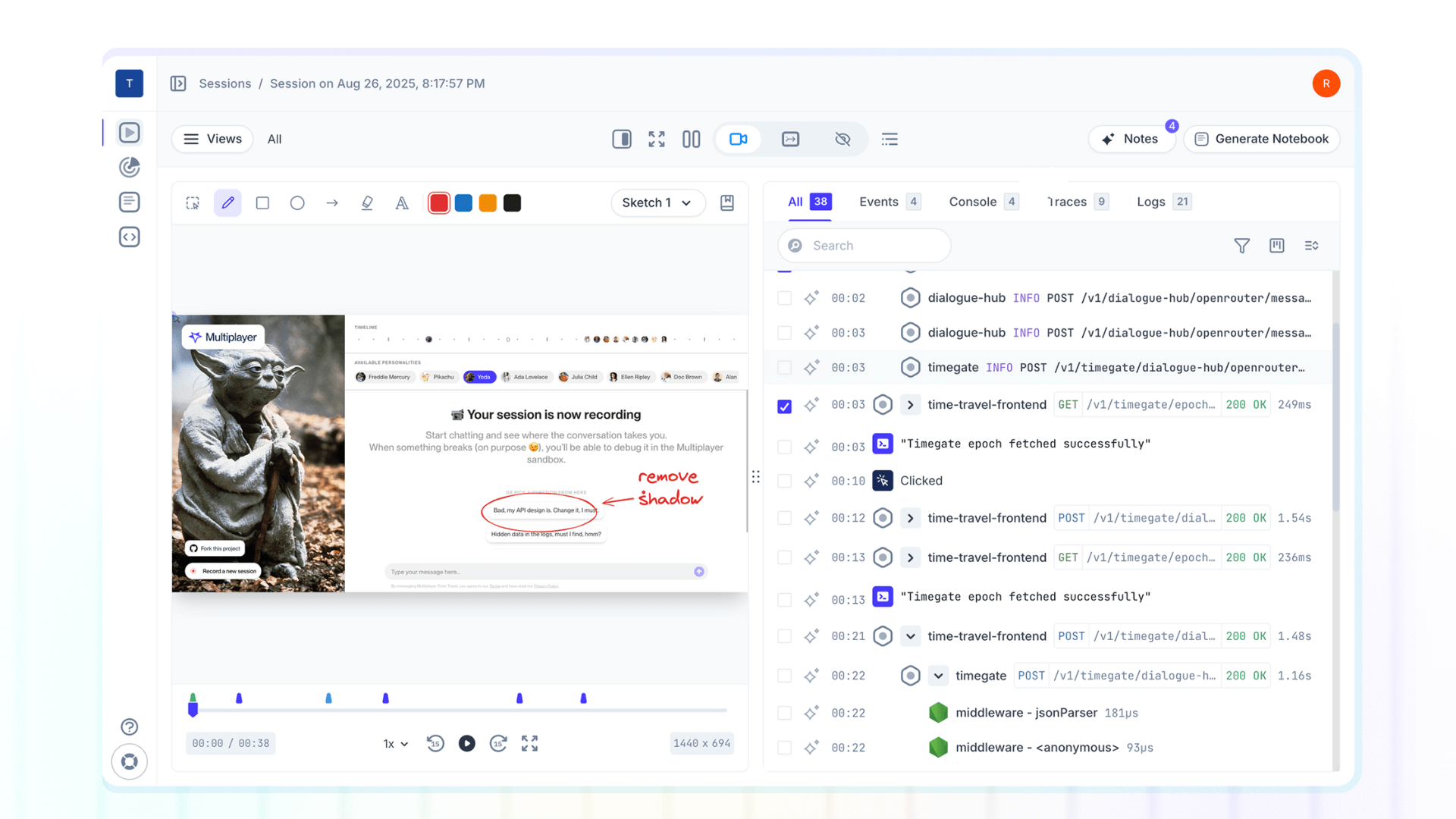

This approach shifts focus from reactive monitoring ("the system is down, what happened?") to proactive understanding ("why is this specific user experiencing slowness?"). Full stack session recordings exemplify this shift: they capture complete user journeys along with all the technical context needed to understand exactly what happened.

(6) Design dev-first debugging workflows

Most debugging workflows evolved accidentally. Support collects what they can from end-users. Escalation specialists add a few notes. Engineers get a ticket with partial logs, a vague user description, and maybe a screenshot or video recording.

Then the real work begins: clarifying, reproducing, correlating, guessing.

This is backward.

In modern distributed systems, developers are your most expensive, highest-leverage resource. Every minute they spend asking for missing context, grepping through log files, or reconstructing what happened is a minute they’re not fixing the problem, improving the system, or shipping value.

Dev-first debugging flips this model. Instead of assembling context, your tools should capture everything by default:

- Exact user actions and UI state

- Correlated backend traces, logs, and events

- Request/response bodies and headers

- Annotations, sketches, and feedback from all stakeholders

This eliminates the slowest, most painful part of every incident: figuring out what actually happened.

A dev-first debugging workflow ensures that the very first time an engineer opens a ticket, they already have the full picture. No Slack threads, no Zoom calls to “walk through what you saw,” no repeated requests for “more info,” no guesswork.

In 2025’s increasingly complex distributed environments, designing your debugging workflows around complete, structured, immediately available context is one of the highest-impact decisions you can make.

👀 If this is the first time you’ve heard about Multiplayer, you may want to see full stack session recordings in action. You can do that in our free sandbox: sandbox.multiplayer.app

If you’re ready to trial Multiplayer you can start a free plan at any time 👇